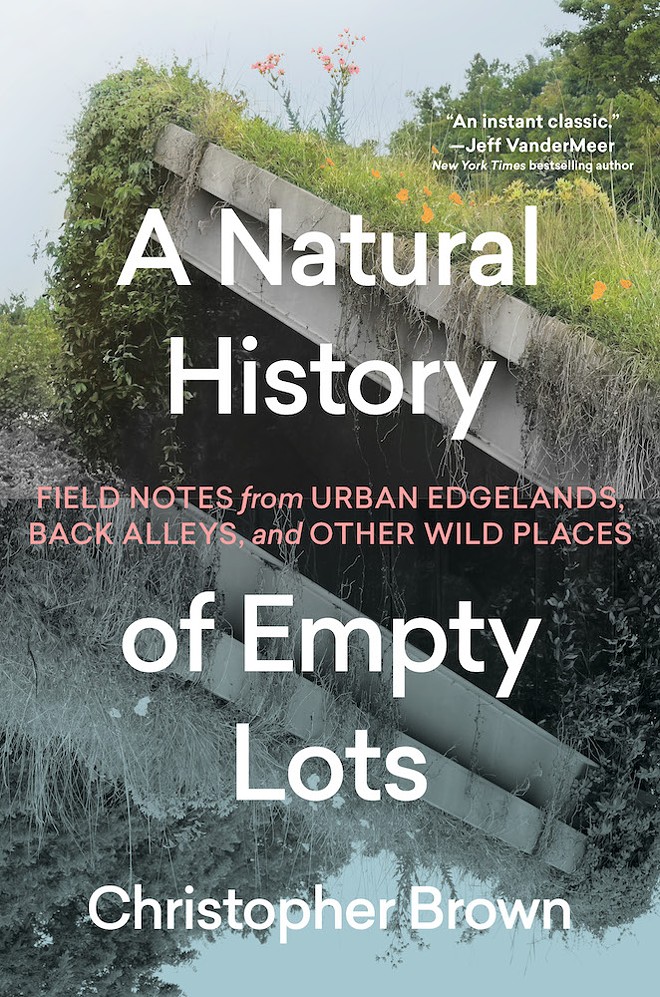

A Natural History of Empty Lots documents Brown’s 20-year experiment traversing, living in and writing about these urban edgelands. Publisher Timber Press has called the book a “genre-bending blend of naturalism, memoir and social manifesto for rewilding the city, the self, and society.” It’s also racked up praise from Pulitzer finalist Kelly Link, bestselling author Jeff VanderMeer and esteemed comic-book writer Chuck Wendig.

Austin-based Brown, who’s also an attorney and an author of dystopian science fiction, will appear at the The Twig Bookshop, 306 Pearl Parkway, Suite 106, for a reading and a conversation with fellow naturalist and author Jennifer Bristol. The free event will get underway at 5:30 p.m. Signings by both writers will follow.

We caught up with Brown via phone to talk about A Natural History of Empty Lots, the book’s origins and how people can carve out time for their own explorations of urban nature. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

At its core, this is a book about place, and you do a great job using vivid, descriptive language to put us there. How difficult was it to get that dialed in?

I’m glad you had that reaction to it. … In this book, I’m trying to weave together some very disparate kinds of writing or narratives. You have the things that are sort of traditional nature writing, that’s very focused on place, very focused on types of life or landscape. But I was also weaving in literary nonfiction or narrative nonfiction and threads of memoir to provide a personal through-line — idea stuff, essay-like stuff.

So, with respect to the writing about place, it’s really challenging, because you want to achieve that effect of describing the very particular thing but also give a reader who’s not familiar with that place a chance to say, “Oh, I can imagine that place in my mind based on this description on the page.” And also you want to help them see their own world and place through a similar lens, if you will, and get the universal from the particular through that.

The landscape of this book is a very specifically Texas kind of landscape. It’s the industrial part of Texas, where you have the sometimes-brutal engineering interventions of the petrochemical industry and other light and heavy industrial activities that sometimes have the unexpected — and at times wonderful — coincidence of preserving little pockets of wild nature within, because they keep all the other human activity out.

For example, nobody goes down to the stretch of the river behind factories because there are big fences cutting them off. Or people don’t typically go paddling in Houston up in the creeks that are feeding into the ship channel because they’re afraid they might breathe something unhealthy.

And so, I was trying to do what my old editor at Harper would call “dystopian nature writing.” Trying to show the world as it is and show the really beautiful things that demonstrate the resilience of nature in these kinds of places, while at the same time, not hiding the ugly bits.

The book grew out of an e-newsletter you published called Field Notes. Can you talk a little bit about what Field Notes was and how that led to the book?

In, I don’t know, February of 2020, right after I finished the last round of editorial revisions on my most recent novel, Failed State, I had been accumulating all of this material from — it’s been 20 years now — walking every day in the urban woods and creek beds and watersheds and whatnot, having encounters with urban wildlife and experiencing this edgeland landscape. And I was thinking, I wanted to do something with that material.

And I was very interested in the newsletter format. I’ve kind of always been interested in that format. I was a newspaper guy before I became a novelist and a lawyer, science fiction writer or whatnot, and I always liked that opinion-column length. And I love that idea of publishing weekly. Almost like a letter to friends, but to friends you don’t know.

When many people look at urban renewal, which you discuss in your book, or even trying to devote more attention to nature, they say, “If only I had the time.” What would you say to people about making time for interacting with nature in an urban surrounding?

Oh, that’s a great question, Sanford. I’d say it starts with just changing how you look at the world around you, and relearning how to see that the very word “nature” embodies an illusion that there’s some separation between us and the natural world, when all of the spaces that we occupy are part of it, and nature is always there. But yeah, if you’re inside a building that we’ve made, it’s still pretty distant.

You don’t need a lot of time to experience nature in the urban environment. You just need to tune in the aperture of whatever time and natural objects are available to you. And it can be as simple as going for a walk and just stopping to pay attention to what bugs are on those flowers near your path — something you might not even really notice unless you stop and focus in on that almost-microscopic world.

Or if you go out for a run or a bike ride, try to alter your route to go to a place where instead of being likely to run into a bunch of other people, you might have a chance of bumping into an early morning coyote. Or a place that will give you a view of some exceptional body of water or remnant of the prairies that once dominated the landscape.

And San Antonio is incredibly blessed with the kinds of places that I think are easy for anybody to access. From the obvious stretches of the San Antonio River, where some of the natural character has been preserved or restored, to places like the headwaters of the Comal River, where there’s been a full-on Blackland Prairie restoration, to the Missions and the areas around there. And there are all the little creek beds and empty lots.

It’s easy to find your nearest creek or a little pocket of urban woods or empty lot. And if you could just go to a place like that, and if you take the little trick of simply just sitting in one spot, if you have 15 minutes — or, even better, half an hour or an hour — and see what manifests around you. If you bring a little stillness, you’d be amazed because the life is there, it’s just usually doing a very good job of hiding from us.

That kind of exploration seems to push back at the notion that you need to be an expert in nature before you start immersing yourself in it.

It’s okay to be naive and clueless — and just be curious. You can look stuff up in a book later. And you’ll better understand it if you’ve seen it and experienced it that way than if your understanding is only based on looking at a picture on Wikipedia.

Early in the book, you write, that the natural world “is more beautiful when it manifests in these fallen places because of the resilience it reveals. But it’s also deeply damaged and scarred, evidence of the way we have remade the world into some butchered cyborg.” It almost sounds like you’re saying that it’s at once beautiful and at once harrowing to experience the resilience and beauty of nature in those liminal urban spaces.

Totally. Yeah. When you find these pockets of genuine and rich biodiversity within walking distance from your home, often it will be in that kind of a place. Where it’s basically some location that was so abused by us through industrial or agricultural or other uses that it’s run out of economic gas, or it’s so polluted where nobody can go there anymore. And nature very quickly takes those spaces over.

And in Texas in particular, very often the kind of nature that takes over is species of plants and animals that are indigenous to this place, because agriculture only really arrived here in the 1820s. And so it’s just all that life, and the memory of that life is still in the land. And the seeds, literally, of that life, are still in the land.

And so when you have those kinds of experiences, of seeing these beautiful species of wildlife that are right at your back door or right there in this blighted yet beautiful brownfield, it fills you with hope when you understand the resilience of nature that it evidences.

But, then, over time, as you start to learn more about what’s really going on there, it often can also fill you with a sense of anticipatory loss. Both in the damage you see from the past, but also when you’re like, “Oh, the reason all these herons are nesting behind this warehouse in this industrial corridor on the urban stretch of the Colorado that winds its way past the east end of Austin must be because there isn’t anywhere else to go.” And the coyotes are here because partly because their rural habitat is ever diminishing.

And then you see statistics like the fact that, as I note in the book, the World Wildlife Foundation — which seems like a credible source to me — says that 69% of the wildlife population of the planet has disappeared since 1970. You hear a number like that and it’s hard to even get your head around it.

Texans, especially, seem to be very in love with this notion of the frontier, the freedom of the frontier. In your book, you point out that the frontier isn’t always someplace outside of cities or population centers. Could you talk a little bit about the false narratives that we’ve created about frontiers?

I think growing up in an American context, we’re deeply invested in the idea of the frontier and the concept that the frontier embodies that wild nature — the wilderness. There’s an idea that truly wild places are out there in some space that you have to travel to get to. And I think we internalize that kind of thinking in ways that are really unhelpful in terms of learning to really understand the natural environment in which we exist.

And while that idea of the frontier obviously played a crucial role in the formation of American identity and the way it informs our conceptions of liberty and a lot of positive things about the way we’ve impacted the landscape and prospered from it, it’s also caused us to be almost unable to see that, one, that wilderness that you’re conceiving of when you’re thinking about the frontier, it’s not there. Yeah, there are national parks. And yeah, I’ve been to Alaska where there’s all this Bureau of Land Management land, not even officially designated as a park, and it’s kind of open.

But the last frontier is literally at the edge of the Arctic, basically, at one end of the hemisphere. Or at the edge of the totally uninhabitable desert regions. Everything else is occupied by us, and the wilderness is now an interstitial wilderness. It exists in the liminal spaces between the zones that we have totally managed to reshape to serve our purposes. And in a way, that’s what most of our parks are. They’re little, liminal preserves we created between our cities and our farms.

So just learning to rethink how you see the landscape around you can really transform how you go about experiencing and connecting with nature. And in the U.S., there’s a lot of good news on that front. The eastern half of the U.S. has reforested tremendously in the past 100 to 120 years … Where what had been cleared for agriculture has often gone back to woodland. Now it’s a mixed sort of woodland. It’s one that’s like woodland suburbia, right?

But the result of that is that two-thirds of the American population now lives within a short walk or drive from a pocket of wild foliage that’s significant, woods or prairie or whatever. And in those places are all manner of other plant and animal life ready for us to experience. They’re ready to change our experience of our own lives with and get out of our own heads — and also to encourage, cultivate, welcome into our reality in a way that both can enrich our lives in an everyday way and help us start to mitigate some of the damage we’ve done to the climate and to the biodiversity of the planet.

Subscribe to SA Current newsletters.Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter| Or sign up for our RSS Feed