As the Los Angeles Times' pop music critic for more than three decades (1970-2005), Robert Hilburn was the type of editor that would edit with the writer sitting right next to him, going line by line, and celebrating an improved sentence with effusive high fives. He applied that same passion to his Johnny Cash: The Life, arguably the ultimate biography of The Man in Black.

As a freelancer in Los Angeles for almost five years in the early '90s, I had the good fortune of working directly under the supervision of "Bob," as we all called him. And he was every bit as Bono would describe him years later in the introduction of Hilburn's memoir Corn Flakes with John Lennon and Other Tales from a Rock 'n' Roll Life—Hilburn wasn't interested in "scenes," but in sounds, and was able to see something in young, flawed bands that gave him fuel, while the bands themselves got inspired by the wisdom of the ever-youthful veteran writer.

"Bob's role as critic was to encourage suspension of disbelief in the audience, but in the artist as well," wrote Bono. "That is an environment in which music grows. He made us better. … Without ever being pious or elitist, he has the Levitical/Jesuitical energy of a keeper of the flame."

Hilburn, who recently turned 74, spoke to the Current on the phone from his home in Sherman Oaks, an LA suburb.

Why another book on Johnny Cash?

I don’t want to sound pretentious, but I wanted to treat Cash like a president, almost. What I found missing from a lot of biographies of celebrities, music or actors, is that they talk about the person’s life but they don’t really talk about the artistry of the person, why the person is important in any way. They’ll say whether the film is a hit or not, but they don’t say why he or she wanted to make the film. Was it good or bad? I wanted to say why he was important, so that 50 years from now, and I think Cash will be remembered 50 years from now, a person will read the book and will get the sense of why he was important during these times. One of the things I liked the most about your book is how, early on, you tell the story of rock ’n’ roll from Cash’s perspective, as a link between country and rock ’n’ roll. That was one of my favorite moments. I loved Sun Records. This [book] combined all my interests in music: I loved country music, I loved blues, I loved rock ’n’ roll, and I was a fan of Johnny Cash as a teenager. The difference is that I loved Elvis, and Chuck Berry, and Little Richard, and Buddy Holly and all of those guys, but they were speaking to me as a teenager, teddy bears, and hound dogs… Cash was only a couple of years older than Elvis, but when I heard “Folsom Prison Blues” he had an adult voice and adult themes, so it really struck me. “I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die…” I was shocked when I heard that. I didn’t know you could say that on the radio!

I was used to people saying, “One, Two, Three O'clock, Four O'clock rock!” “I want to be your teddy bear” or “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On.” There was a lot of sexual terms but not a lot of adult darkness stuff. There was something serious about Cash. I heard a lot of country music, but he wasn’t like other country stars. That’s one of the main things I tried to answer with the book: why was he different? Why did he have a sense of artistry? Coming from a cotton patch in Arkansas and entering a country field where no one else before him, no matter how big the star, had no more ambition than another hit in the jukebox, why was Johnny Cash different? In all my years as a journalist with the Los Angeles Times I pretty much knew everything. I interviewed Lennon, and Dylan, Springsteen, Bono, Stevie Wonder, Michael Jackson… And I thought I could get a pretty good read on people. I thought that, if you talked to somebody, you had the final answer, that they were the final authority. But when I started writing the book I realized how little we know about celebrities and how much I didn’t know about Johnny Cash, even though I was around him over and over and over again in his life, doing stories about him. Celebrities choose to tell us what they want us to hear. I don’t really know what Bob Dylan is really like, even though I’ve interviewed him a dozen times. But when writing this book, I would find out that things [Cash] said were just not true, and I don’t think he was trying to lie, but make the story a little bit more interesting, so he would embellish upon it. And the people around him, everyone sees something different. And there would be little things, like the first time he flew into Memphis, after being in the Air Force; [someone] says he came to Memphis on the Greyhound bus, [San Antonio’s] Vivian [Liberto, Cash’s first wife] says he flew into the airport, Cash said he flew but Vivian wasn’t at the airport. So you have to talk to so many different people to figure out what likely happened. So at one point you have to be sort of like a judge to the whole thing. Those are the simple things, but the hard part is when there are significant things and you’re trying to piece together what the truth is. I wasn’t within 50 miles of what Johnny Cash’s life was really like. His personal life turned out much darker than I thought it was. He had burdens, and guilt, and drugs, things that weren’t quite honorable, and I was really surprised. But at the end of the book he comes off as a hero, because he keeps fighting through all that stuff to make music that inspires somebody. I kept telling myself, “Oh my gosh… should I tell people about this? Is this too private or not?” Some members of the family didn’t want you to say things that might hurt their dad’s image, but [daughter] Rosanne Cash was very good about this. She said, “I don’t care how uncomfortable it makes me feel; if it’s the truth, tell the truth.” That was very helpful. It was a difficult journey but I just loved every minute of it. (continues on the next page)

You’re the one who taught me about ethics in journalism, not going backstage, keeping a distance from the people you write about. Yet you once “confessed” to me that with John Lennon it was difficult not to get too close because he was such a special person, so you, John and Yoko developed a close friendship, yet you never stopped being critical of him when you had to. In comparison, what was your relationship with Cash like?

I first met Cash in 1966, or ’67. I had just started writing about country music for the LA Times as a freelancer. I wanted to do rock ’n’ roll but there was already somebody writing about it. I did a review of Cash at the Long Beach Auditorium, I think. In those days there wasn’t a publicist there, you had to go backstage and knock on the door, and hopefully they’ll answer and talk to you. I remember knocking on the door and, “What??!!” His voice came out, he was in really bad shape at the time, he looked awful, his voice was raspy. I walked in the dressing room. He was alone, he was wiping his hair, jittery motions. I thought he was just hyperactive; I didn’t realize it was the drugs that were talking. After that we met at Folsom, there was a graciousness, a warmth about Cash, especially by ’68 or ’69, when he was getting off the drugs. He was a relatively shy person, he would kind of retreat in the dressing room or at a social function, he’d let June take over. But he always made me feel comfortable, he’d sit down and talk to me. We both came from small towns, so I think that helped. And secondly, I was somebody from a big newspaper who was paying attention to him, and that really impressed him. He’d always talk to DJs who’d tell him, “Oh, we love your music,” but here was someone from “the Los Angeles newspaper.” The guy in the Air Force who taught him how to play guitar came from my same town. I spent a weekend with him and June at the Carter Family cabin in Virginia, just six months before their death, and that was a really important moment, because I wasn’t planning to do a book, but he talked a long, long time about regrets in his life, and it helped me understand a lot of things about him. I loved John Lennon because he’d make you feel comfortable right away; he’d sit down, have fun, you could talk about Elvis, and Johnny Cash, and things he loved. Johnny Cash [wasn’t] as outgoing as John Lennon but he’d make you feel comfortable in the same way, he made you feel you were talking to a real person. In all the years I interviewed people, I think I took my mother to two or three shows, and I never took her backstage because I didn’t want to go backstage. But one day I told myself, “I think she’d really like to meet Johnny Cash.” She loved Johnny Cash, and everybody loved Johnny Cash back in that day. It was amazing he’d get such a wide following. So I took my mom because I knew he would understand I wasn’t trying to be a groupie and he’d be gracious to her. And he was, and that was a great snapshot of him. He wasn’t the kind of people that would go out of his way to meet people, he was kind of shy. But he came over to her, shook her hand and said, “Anything I can do for you? I hope you enjoyed the show.” I wouldn’t have taken that chance with most entertainers, because I think most would’ve brushed her off.

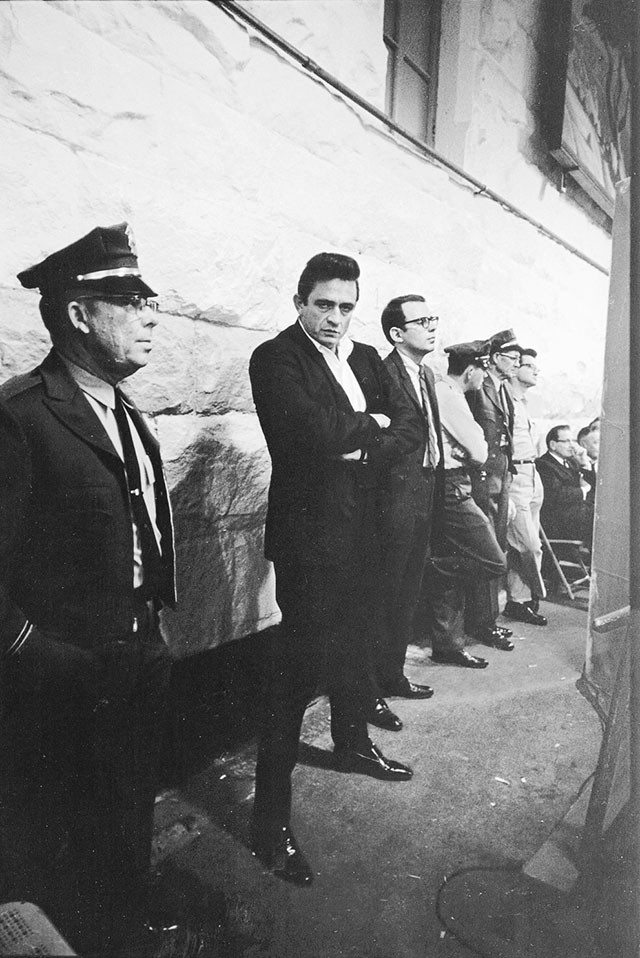

What’s the story of the famous Folsom Prison photo?

I was just there trying to write a story and I was looking for angles. He was standing there trying to sense the audience. He was nervous, this was an important step in his career, and I was just looking around for things I could use in the story. I thought it was going to be an exciting moment, but who knew it would be a landmark album?

He spent relatively a small amount of time in San Antonio, yet those were key years in his life.

That was so important, because he came out of Dyess, Arkansas, which was like 50 miles from Memphis, and he had been out of Dyess four or five times in his life, a small town of 2,500, and he didn’t have a lot of self confidence. His father never really thought he’d amount to anything. He’d gone to Detroit to try to work at an auto factory and had suffered a lot of anti-Southern bias, and he didn’t know if he’d suffer the same bias in [SA]. He was very nervous going to the Air Force, but it turned out he did very well and passed all these tests at Lackland. He was a star, other [soldiers] would come up to him and ask for his help. That did great for his confidence, and the second time he came to [SA] he had no experience with women, he barely had girlfriends in high school, and he meets Vivian at this roller rink. He knew how to roller skate because he worked at a rink in Dyess, but he pretended not to know so she could help him stand up and so forth. He was looking for a girlfriend so he could tell the guys at the barrack, “I got a girlfriend,” he could write her letters, and he felt very deeply in love very quickly. It did great for his confidence that someone from outside of Dyess could be interested in him. When he went to the Air Force he would write her a letter once or twice a day, everyday for three years, more than 1,000 letters.

She was hoping they could live in [SA], because her family was there and had strong roots in SA, but he wanted to go to Memphis because it was closer to Dyess and his brother was already there, and that’s how he ended up in Memphis. And in SA would’ve been harder to start a music career. But he didn’t go to Memphis to start a music career, but because his brother found him a job.

In spite of all the drama in his life, he was a lucky guy, being in the right place at the right time throughout his life.

He sure was. I even thought of giving speeches on “Johnny Cash’s luck.” There are so many instances… Can you think of a specific one?

Well, when he happened to unknowingly be driving around Sun Studios at such an important time in music’s history…

Oh, yes… Well, the first lucky incident is just him going to Memphis. He goes to Memphis because he wants to get a job there. But the truth is that, for a young, unschooled Johnny Cash, there isn’t a better place he could’ve picked than Memphis. Sam Phillips is just starting Sun Records, and the first day [Cash] arrives back from Germany Elvis cut his first record there. Johnny Cash loved that record. He saw Elvis appear at a drugstore opening singing the song, and he asked him, “How do I get a job at Sun Records?” And he called Sun Records and they kept putting him off day after day after day. After work he would go home and drive by Sun Records not knowing it was there, until the day he finally went to see Sam Phillips and [Phillips] said, “OK, sing some stuff, maybe we can make some music together.” Had he moved to a different place, he would’ve probably not made it because [Cash and the Tennessee Two] weren’t that great, not at all like other stars of the time. And the other important thing is that, by recording with Sun Records, he always had a rock ’n’ roll audience interested in him. Had he gone to Nashville and made those same records he would have never made it. He’d be considered a country star like Marty Robbins or somebody like that. By going to Sun he was always part of that Elvis Presley/Jerry Lee Lewis world. So when he goes back to Folsom Prison in 1968 Rolling Stone is all excited, because here’s a rock and roller doing that kind of stuff. If Marty Robins had done the same thing, [RS] would not have cared.

OK, so that was the first stroke of luck, and the last one was meeting Rick Rubin.

That sure was. But the biggest one of all, probably, is when he’s in Germany and in his first week he sees a movie called Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison. Had he gone to Germany a week later, he would have never heard of Folsom Prison and wouldn’t have written the song. But even then, he gives up on writing the song, and one day he’s walking down the barracks and a guy was listening to a song he had bought on a whim the night before, “Crescent City Blues.” Cash hears that, goes over to the guy and says, “Could you play that again?” And he pretty much copied, or stole, or however you want to put it, but so much of “Folsom Prison Blues” is from “Crescent City Blues.”

So if that guy hadn’t bought that record, [Cash] would not have heard that song. But by 1993 he had been dropped by Columbia Records, he was doing terrible in Mercury Records, he had no more faith that people even cared about him, he thought his career was over and his legacy forgotten, and this rock ’n’ roll/rap producer walks into a show at the Rhythm Café in Santa Ana… He had been playing arenas in his life and now he’s playing these little cafes. June Carter said, “This is ridiculous, John. You can’t work with this guy, a rock/rap producer.” But [Cash] had no alternative. When I talked to Rick that is the thing that struck him the most about Cash’s reaction—the fact that Cash was curious. “Why would anybody be interested in me? My career is over with.” So Rick’s biggest challenge was rebuilding Cash’s confidence in himself. And that’s a really inspiring story, to see how these two guys became so close and how Rick struggled, and struggled, and struggled to get Cash to believe in himself again. And once John started to believe in himself, he was able to do some of the best work of his life, at the age of 65.

Recently, some young local bands here did a Johnny Cash tribute…

Really? Where was that?

Here in SA!

That’s great! I think Rick Rubin brought him into a new generation of people. If it hadn’t been for the Rick Rubin years, he would not have had the same stature and the impact on people as he has today. The old people are gone and their influence has gone away, but it is the young people that got turned on by the Rick Rubin era that are still here. He appealed to so many different people. Rockers and punksters, and the reggae crowd are attracted to him because there was an essential truth in what he was saying. People believed Johnny Cash. He was very good at empathizing with people, especially with the underdogs, because he was an underdog himself. He had been in trouble with the law, so he could relate to people in prison whenever he sang in prison. He knew how to design shows in order to communicate directly to his audience, either in prison or at the White House. June didn’t want him to release the “Hurt” video. “John, your fans are going to think you’re destitute,” and all that, but he thought it was a piece of art. He was so brave to put that out.

Reading the book, it’s obvious that you really loved and admire Cash, but, as usual in your work, you had no problem being critical of him, and it is clear that Cash did make some awful albums…

Oh yes, he had bad albums. After the superstardom of the ’70s, the prison album and the TV show, he’s got a son now, he wants to enjoy that part of his life that was a blur in the ’60s. He was on drugs and felt guilt every day of his life about leaving his daughters. If you look at the picture in the cover of the book, those sad eyes… He always seemed to have those sad eyes. The sadness over leaving his family and his brother dying… There was a lot of sadness in his life. So in the ’70s he wants to devote his life to his family, invites the girls to come back to Nashville to be with him, he has a son, meets Billy Graham, goes out with him in crusades… In the ’60s music was his only comfort, he devoted night and day in writing better songs and recording concept albums. By the ’70s he had started to relax, paying attention to all the things he neglected in the ’60s, but he now started neglecting his music. And slowly the albums kept getting weaker and weaker. By the time he realizes this and tries to correct it, country music had left Cash behind. You get all these Kenny Rogers, and country radio won’t play Cash anymore. So he goes down and down and down. Once in a while he’d come up with a good album, but his confidence was gone and Columbia drops him. So the period from ’75 to ’90 or even 1993 was a very uneven period for Johnny Cash. When he wanted to think of the music again, it was too late. There were good tracks here and there, but for the most part those albums were poor. But another very important thing happened just a month before he met Rick Rubin. U2 invited him to the studio to sing the lead in “The Wanderer.” Written by Bono, it’s a gospel song. Cash was very intimidated because he had no confidence and here was the world’s biggest group asking him to sing with them. And he did it and got all this acclaim, and the album was a big hit, and Rolling Stone gave it a good review. That really helped him get his spirits up a little bit before Rick Rubin came in.